“Paradoxically, at a time when some architects, lighting designers, graphic designers and sculptors are becoming increasingly aware of neon’s possibilities, there are few if any young people learning the craft of glass bending.” – Rudi Stern, “Let There Be Neon” (1979)

Rudi Stern was an American multimedia artist most widely known for his work in neon. His observation holds just as true – if not more so – today than it did in the late seventies. Creating neon signs is a fascinating art that requires far more skill and dexterity than might first be apparent. Which is why we were beyond thrilled when our friend Dave Waller at Neon Williams agreed to sit down with us and talk about the craft of making neon signs and how their Somerville shop created the neon Mothership sign for our clients.

But let’s back it up and start at the beginning. We were working with our super cool clients, Revival Cafe + Kitchen co-founders Liza Shirazi and chef Steve “Nookie” Postal, to help them brand their new restaurant, Mothership, in Cambridge. They had awesome ideas about the aesthetic they wanted to create; inspired by a love of vibrant, playful colors – and the feelings of comfort and familiarity they induce. They wanted their restaurant brand to be casual and playful, but still modern and clean. Classic, but open to pushing limits. So when they said that they wanted something iconic, arty – yet nostalgic – above the bar, we knew it had to be neon.

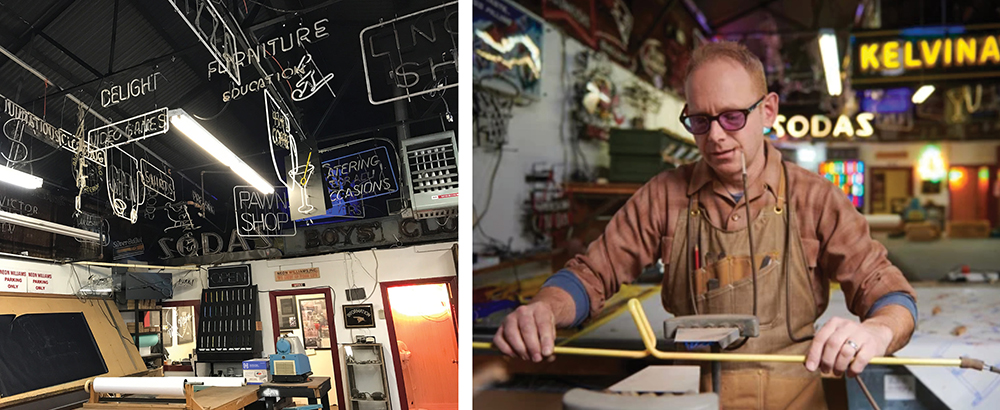

Enter Neon Williams. We collaborated with this Somerville studio to create the sign, and the experience was so fascinating that we wanted to share some of it with you by way of the following conversation with Neon Williams’ Dave Waller.

Neon Williams has a long and impressive history creating custom neon signs. Have your production techniques changed since you made, say, the Citgo sign? Any other notable signs designed by Neon Williams that we might have seen around town?

Our production methods haven’t changed significantly since we opened in 1934. There’s been a few small innovations since then, but overall we still make paper patterns by hand, bend and process the glass all by hand. From spectaculars like the Citgo sign and the Paramount Theater to small window signs, you’ll find our work lighting up all of New England and beyond.

There aren’t that many neon signmakers left in Massachusetts, and yet we’re seeing more and more neon signs again. Are new custom designs injecting a fresh, artistic touch to a 20th century trend?

I think of neon these days as more of a craft, much like making horse saddles – there willl always be neon, but never like it was decades ago. Because it’s hand made, it’s likely going to be a bit more expensive, but it’s got a beauty and appeal that fake neon just doesn’t have. It’s got an extraordinary long life – much, much longer than the new technology products promise. We’ve got some working signs in our shop that are approaching 100 years old! And it’s very energy efficient with the modern ballasts we use.

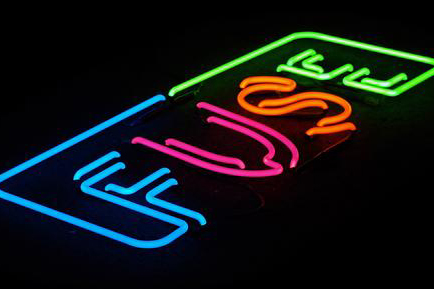

Our collaboration with Neon Williams focused on creating a custom neon sign for our client, the new restaurant Mothership. They are such a fun group to design for – they love vibrant, playful colors and bold, iconic style. Does this aesthetic just call out for neon??

We love the Mothership aesthetic! People who love color, who love fun seem to really appreciate neon. Many of our clients push us to make something totally unique and we love the challenge – it makes us better!

In your mind, are neon signs always associated with “retro Americana” style?

Neon can certainly convey a retro look, but it’s just as easy to make modern signs and even use it as lighting. We have biotech companies, advertising agencies and high-end retail shops who ask us to make modern, stylish signs.

Can you walk us through your process? Let’s say an awesome little creative agency in Boston reaches out asking for a custom neon sign for a very cool new restaurant in Cambridge. What’s next?

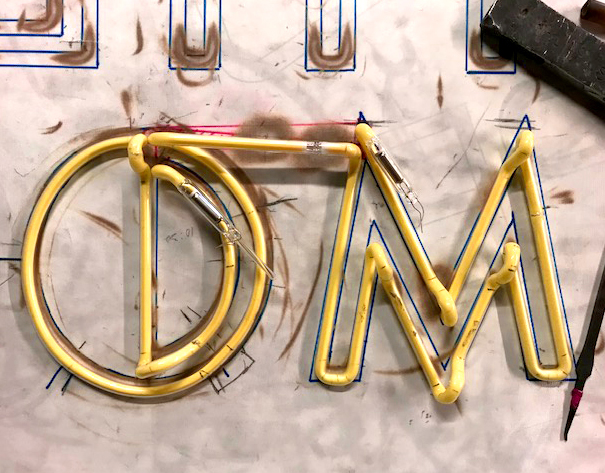

The Mothership sign began with creative discussions between our team at Neon Williams and the LLM Mothership team. Lynn Waller – who handles our design, layout and absolutely everything else – coordinated the project and showed LLM how their logo design could be rendered in neon at the various sizes that were under consideration. We’re really glad they went with the double-outline. It looks fantastic. Once the design was finalized, a color was chosen. From there, Tony Dowers, one of the shop’s benders, developed the full scale paper pattern for printing.

From those patterns, our neon benders create a bending pattern on fireproof paper to determine exactly how the letters will be formed, where the electrodes will be placed, and how the letters will be spliced. The pattern is made in reverse, to allow for the tube bender to lay the hot glass directly onto the pattern and make adjustments before the glass cools. Long, curved bends take much longer to achieve than 90-degree bends. The glass is heated only in the area to be bent, and air is puffed into the tube to keep it from collapsing while heated.

The individual letters are spliced together, electrodes spliced on the ends, and hooked up to a processing table. Air is pumped out, the tube is purified with 50,000 volts of electricity to remove all foreign material, and a small amount of Nobel gas inserted. Different gasses produce different colors. The tube is then “baked in” with more high voltage until it gradually takes on the final color.

And finally, it’s time to hang and install the sign at the restaurant. Stay tuned for the final photos… Mothership is opening soon at 125 Cambridgepark Drive in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

And that is the story of how this design studio worked with Neon Williams to create a very cool neon sign for a very cool client. If you want to see more about the full Mothership brand design, we’ve got a post about it here.

Footnote: Neon technology is over a century old, yet its science is awfully hard to understand. We won’t get into it here, but check out this article if you’re interested in learning more.

Also, this process began in March 2020 before social distancing was being routinely practiced.